Although my son has loved all the time he’s been spending with my husband and I since March 13th, when our city closed schools and daycares, I know he’s also confused about what’s going on.

The hardest thing for him, I think, was that we had to celebrate his 4th birthday party in quarantine. I warned him that his friends weren’t going to be able to come because of the virus and he seemed to understand and seemed a bit disappointed but overall I thought he was OK with it. We baked a cake, a rainbow funfetti cake, at his request. I wrapped up all his presents and then some– I wanted him to have an enormous pile of presents so I even wrapped up things like boxes of Teddy Grahams! We put hats on his stuffed animals and sat them around the table, blew up balloons.

But after the presents, he didn’t seem to want to start on the cake. I asked him, “Honey, don’t you want to eat your special rainbow cake and blow out your candles and make a wish?”

He looked at me and started crying, “I guess my friends really aren’t coming? Not even for cake?!?”

I hugged him and said, “No, sweetie, they can’t because of the virus but when the virus is over, we’ll have a giant party for everyone!”

“I just thought they would come for my birthday,” his chin wobbled.

“Well… maybe that means that you get two slices of cake?” I answered.

I’ve done my best to keep his spirits up, but there are moments, and it’s hard to explain what’s going on to little kids.

I’ve found a couple of resources, though, that help, starring some of my son’s favorite characters.

Elmo from Sesame Street practiced social distancing. And both Elmo and Big Bird also made talk show appearances! Sesame Street has a number of other suggestions and ideas of how we can care for each other during this difficult time. Honestly, even as an adult, I find Sesame Street a happy oasis right now and I think it’s great how the show is helping families with young children cope.

Another one of my son’s favorite characters, Daniel Tiger, has helpful songs about resting when sick, and shows how to wash hands.

For older kids, Axel Scheffler, author of the beloved Gruffalo, published a free e-book for kids on COVID -19.

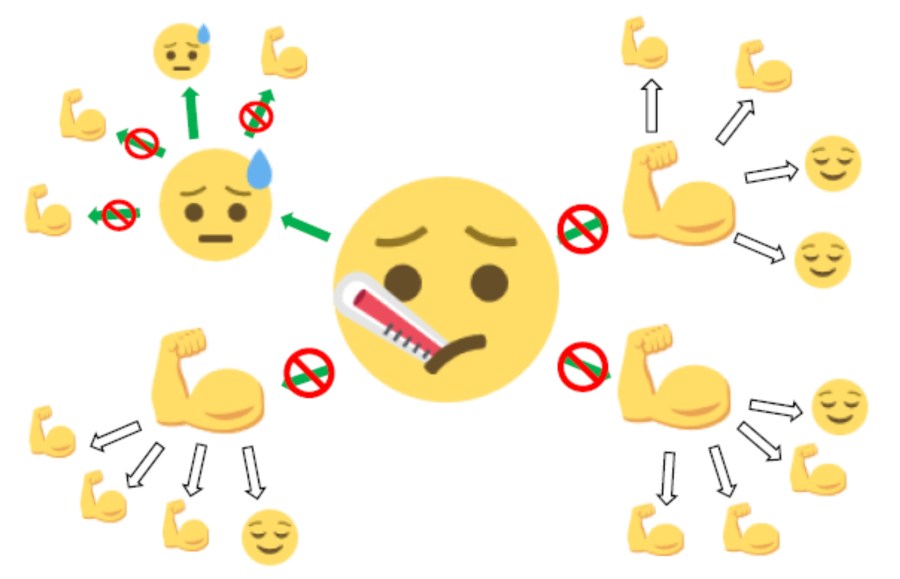

Another show my son loves is Cocomong. It’s a show out of South Korea, available on Netflix, and a bit strange, but overall I think the messaging seems to be really helping my son. The show teaches kids to eat well, get enough rest, brush their teeth, wash hands, and exercise– basically, some light-hearted social engineering that’s been helping my son to eat his vegetables and learn what probiotics are. The hero, Cocomong, fights the Virus King in almost every episode. The Virus King and his sidekicks do things like lure the characters into eating candy instead of vegetables, pollute the air or water, and just generally trick everyone into bad habits which they only realize once they all start to become sick or unhealthy.

We’ve therefore personified COVID-19 as the Virus King in our house– pretty appropriate for a deadly coronavirus*, right?

By far the hardest thing has been trying to help my son understand that you can’t see the virus, that it’s so small it’s invisible– yet something tiny can hurt us badly, and that’s why our lives have all changed so much.

Have you found any other resources that have helped the kids or families in your lives?

*’Corona’ means crown.